Boise River Flood Control District #10 was formed by a group of proactive farmers in December 1971. To commemorate Flood 10’s history, we created a 4-part series of stories and photos to inform and educate the public about how and why the district was formed, share many of the challenges that river managers faced then and now, including flooding and riverbank repairs, and collaborative efforts to manage the Boise River for the benefit of everyone in the future.

Who is Flood 10? What do they do? Flood District 10 conducts winter maintenance on the Boise River (from Plantation Island in Boise to Caldwell) to maintain the Boise River channel and prevent damage to private and public property. Flood #10 also works with private landowners on streambank repairs.

Here is Our Story Series

For more information about Flood Control District 10, contact Mike Dimmick, District Manager [email protected](link sends e-mail)

For feedback on the stories, contact Steve Stuebner [email protected]

Part 1: Flood 10 Evolves Over 50 years to Chart More Proactive, Progressive Management of the Boise River

- By: Steve Stuebner

- Feb 21,2021

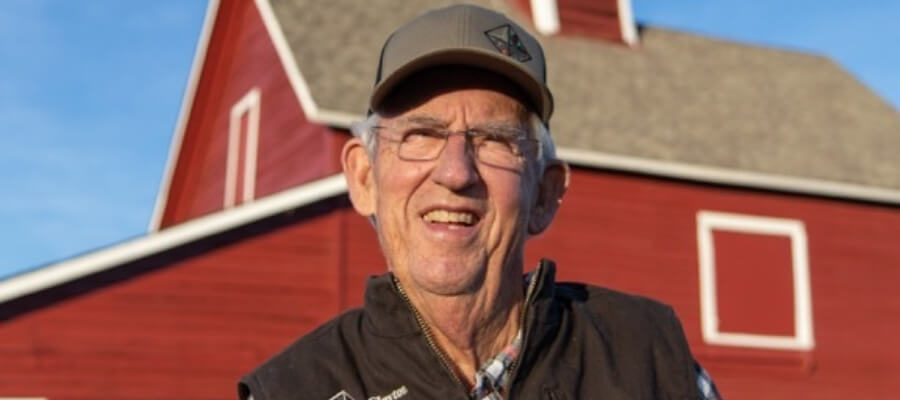

Bill Clayton dipped his toes into the Boise River before his first birthday. He spent every summer on his grandparent’s farm on the river near Star. Clayton milked cows before dawn and looked for ways to go fishing when the work was done.

As a Captain in the Marines during the Vietnam War, Clayton flew Huey gunship helicopters. Later, he and his wife, Diane, moved to a river ranch across the river from his grandparents, Lazarro and Ines Urrusuno. They raised their family there and built a large wholesale tree farm business from scratch.

Clayton joined the three-member board of Flood Control District #10 in 1989. He’s served on the board for more than three decades.

In the Marines, when he was learning how to fly, he’ll never forget his flight instructor sitting behind him, hitting Clayton on the head with his clipboard, saying, “You fly the airplane, get ahead of the airplane. Don’t let the airplane fly you.”You fly the airplane.

After Clayton got involved with Flood 10, he felt like “we’re always just reacting to the river. How can we ever get ahead and be more proactive in managing the river?”

Now, as Boise Flood Control District #10 celebrates its 50th anniversary, Clayton feels as if the district is finally getting somewhere with proactive management. The district is developing a Boise River 2-Dimensional Model Tool in cooperation with the Army Corps of Engineers and more than 10 partner entities that have a stake in Boise River management.

This high-tech tool will allow Flood 10 and partner agencies to run this new and innovative computer model to see what kind of impacts will occur to the Boise River floodplain, community infrastructure, and adjacent property when simulating flood flow above 6,500 cubic feet per second (CFS). The impact areas reflect off the map with bright colors and highly detailed lidar aerial photography. The model runs will show where flooding might affect the private property and public assets like river bridges, how sediment flows and gravel bars may be moved or increased by flood flows, and what kinds of solutions might exist to avoid the damage.

“I’m excited as hell about the Boise River 2D Model Tool,” Clayton says. “Finally, we’re getting to the point where we’re flying the airplane. We’re getting ahead of the curve.”

“We’ve gone from a reactionary agency – something happens, we go out and fix it – to one that’s trying to get out in front of the issues, look at potential flood flows, predict where we’ll have problems, and work to address those problems,” adds Mike Dimmick, District Manager for Flood 10.

“Close to 2 million yards of gravel are moved by the Boise River during spring flows every year,” Dimmick says. “That’s a lot of material. Most people have no idea that occurs. All of that gravel and sediment movement has impacts up and down the river. With the model tool, we can pinpoint those areas more easily and develop solutions to address the issues.”

Flood 10 is responsible for doing channel-maintenance activities on the Boise River during low-flow periods in the winter months inside its jurisdictional boundaries – from the Plantation Island area in Garden City downstream to the city of Caldwell – to protect private and public property.

The Boise River is the centerpiece of the City of Boise. It’s widely valued by people up and down the river for farming, ranching, irrigation, fishing, recreation, floating, surfing, fishing, residential development, and more.

Under the original order, Keith Higginson, the Director of the Idaho Department of Water Resources in December 1970, concluded that the creation of Flood Control District #10 “is necessary, practicable and feasible, in order to provide control of the Boise River and its tributaries in the affected area to protect life and property, preserve the public health and welfare and conserve and develop the natural resources of the State of Idaho.”

Along with the creation of the Flood District came the authority to levy a small tax (.06%) on property owners who lived adjacent to Boise River or nearby to cover the cost of maintenance and river-bank stabilization activities. About 25,000 acres of land were included in the original boundaries of the taxing district; those boundaries have not changed substantially since.

It should be pointed out that the words “Flood Control District” are a bit of a misnomer for Flood 10, officials said. The actual control of Boise River water flows during the spring months when flooding can be imminent, is the responsibility of the Army Corps of Engineers and Bureau of Reclamation via the storage and release of water flows in three large reservoirs upstream of the City of Boise. Lucky Peak, Arrowrock, and Anderson Ranch Dams all have a combined capacity to store about 1 million acre-feet of water.

Clayton doesn’t like the name, either. “Let’s be honest, no one controls a flood. You try to manage floods and prevent the damage as much as possible. That takes a team effort, and we’re part of that team. But mainly, we are a river maintenance district,” he says.

The work of Flood 10 is regulated by state and federal permits, allowing the removal of tree snags in the river channel, trees about to fall in the river, and other debris during the winter low-flow period between late October and March. This is a time when Flood 10 works to assist landowners with streambank repairs and do maintenance on the river channels to prevent damage to public and private property.

Fifty years ago, when a District Court judge granted the petition to form Flood 10 in December 1970, farmers were most interested in keeping the channel clear of trees and debris. The interests of trout anglers, recreational river floaters and others were not top of mind, at least to the three farmers who served on the original board, beginning in 1971. This was a time when concrete rip rap and old car bodies were used to shore upstream banks, bulldozers were used to push up gravel to maintain irrigation diversions, and the Boise River Greenbelt was in its infancy.

Over time, as broader discussions occurred via forums like Boise River 2000, Idaho Environmental Forum annual Boise River float trips, and the Boise River Enhancement Network (BREN), Flood 10 officials know they have to balance a multiplicity of interests.

“Boise River 2000 got us talking,” says Clayton. “There was very little communication and not much trust between the different groups using the river.”

“When I got involved with Boise River 2000 in the 90s, I had no idea what a flood district was,” says Tom “Chel” Chelstrom, long-time manager of the Boise REI store, now retired, and an avid canoeist.

“Since that time, great progress has been made,” Chelstrom says. “It’s gone from we’ve got a job to do and you’re not part of it, to today, where we’ve got a job to do, and how can we all do it while accommodating all of the other interests in the Boise River.”

All of those interests make managing the Boise River “more complex than ever,” Dimmick says. “But we are committed to maintaining as natural a river corridor as possible while staying true to our responsibilities as a flood district.”

Part 2: History – Boise River Farmers Create Flood Control District #10

- By: Steve Stuebner

- Feb 21,2021

Back in the late 1960s, Boise River farmers were focused on keeping the river channel clear of trees, debris, and other obstructions so they could access river water for irrigation. They also worried about how spring flooding affected their private property and croplands.

So it makes sense that farmers would be the ones to champion the formation of a flood control district on the Boise River in 1970. “No one else had as strong of an interest in managing the Boise River channel as the farmers back in those days,” says Bill Clayton, Chairman of Flood 10 since 1989.

Historical documents in the archives of the Idaho Department of Water Resources show that the original petition to form Flood Control District #10 was brought by Albert Wolfkiel, a farmer and member of the Boise Soil Conservation District. Ivan Cane, a farmer and chairman of the conservation district testified in favor of forming the flood control district, indicating that the Boise SCD had been discussing the matter for some time.

A hearing notice related to the formation of Flood 10 indicated the purpose of forming the district as follows: “The object for the organization of the Flood Control District is to provide means insofar as practicable and economically feasible to control floods of the Boise River in Ada and Canyon counties and for the object and purpose investigation of all reasonable and proper methods for the control of the said stream. That all of the said things to be done in the way of controlling the high waters of said Boise River will be conducive to the public health and welfare and to reduce damage to property and endangering lives during such high water seasons and that such proposed methods or systems of flood control are property and advantageous methods of accomplishing such relief.”

It’s notable that historically, most people did not want to build homes or businesses close to the river because it was prone to flooding and causing damage on a regular basis prior to the completion of Anderson Ranch Dam in 1950 and Lucky Peak Dam in 1955.

Floods were massive with major impacts. A freak winter storm with warm rain on top of snow created a flood of 44,000 CFS on the Boise River in December 1964, for example. The April 1943 flood of 25,040 CFS caused so much damage that it inspired the discussion to build Lucky Peak Dam. Damages from the 1943 flood totaled $997,350, according to the Army Corps of Engineers. The dam was approved by Congress in 1949; the cost was $19 million (1955 dollars).

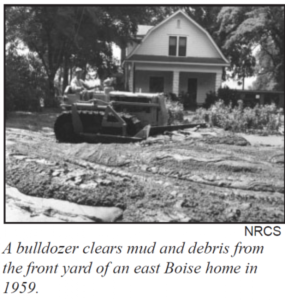

In 1959, a fall heavy rainstorm dumped 2.23 inches of water on top of recently burned lands on Shaw Mountain, causing mudflows to wash into the city of Boise from Cottonwood Creek, Maynard Gulch, and other streams that flowed out of the eastern foothills. Photos of bulldozers pushing mud out of the streets of Boise made a lasting impression. Residents had to shovel 10-inch-deep mud off sidewalks and driveways.

A video documentary about that whole ordeal, available on YouTube, was titled, “When the Pot Boiled Over.”

“Never in the community’s history had there been a flood such as the big mud bath of 1959,” the narrator said in the video. “Thousands of tons of soil and debris were spread over the city of Boise and surrounding country.”

Peak flows of 19,000+ CFS occurred multiple times in the decades prior to the construction of Anderson Ranch and Lucky Peak dams. During the big flood of 1983, 24,290 CFS came roaring down the Boise River as measured at Diversion Dam. After the flows were regulated, the 1983 flood sent 9,840 CFS down the Boise River corridor, flooding out thousands of acres of land and damaging private and public property.

The primary purpose of Anderson Ranch, built by the Bureau of Reclamation, was to provide more irrigation storage water for farmers, along with some flood-control benefits and recreation benefits. Lucky Peak was built by the Corps of Engineers primarily for flood-control purposes in addition to recreation, hydropower, and irrigation.

(Arrowrock Dam, by the way, was one of the first dams built in the western United States by the Bureau of Reclamation from 1911-1915. It was built primarily as a water-storage project for irrigation. It was the largest concrete-arch dam built in the world at the time, according to Wikipedia.)

Even after the three dams and reservoirs were completed, Boise River farmers complained that the Boise River channel had less capacity to fulfill their full water rights because of gravel, trees, or debris blocking their diversions.

“It’s getting to the point where there’s no channel anymore,” lamented Jess Urrusuno, a district board member. “I feel we need a freer hand as to where we can repair. We should be given some of the Boise River as a working stream.”

Most people testified in support of forming Flood 10 in two different hearings, one in May 1970 and one in July 1970. Most people who testified were farmers who lived next to the river. A few others testified, including the Idaho Fish and Game Department, the Boise River Watermaster, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Idaho Wildlife Federation.

Farmer Ivan Cane, responding to concerns from IDFG that the farmers wanted to turn the river into a canal, said, “We’re not going to do that. We didn’t do that before, and we’re not going to do that now.” But Flood 10 board members wanted a freer hand to manage trees, gravel, and debris in the river, he said.

June Walters, who lived close to the Boise River, testified that “this matter of keeping things natural for nature lovers, etc., you’ll find the original nature lovers were farmers. Otherwise, they wouldn’t still be farming. They love the soil. They love the land and all that grows there, including the animals and the birds…. But the (farmers), they don’t want their homes washed away, nor their making of a living.”

The petition to form Flood 10 was approved by then-IDWR Director Keith Higginson. The first three commissioners to run Flood 10 were all farmers:

- L.C. Mace, Eagle

- Ivan Cane, Meridian

- Harry Burger, Caldwell

A bond of $5,000 was approved for Flood 10 as its initial budget. A map of the taxing district was provided, a relatively narrow strip of land on either side of the Boise River from the Plantation Island area in Boise to Caldwell. The original commissioners were appointed by Higginson on Nov. 25, 1970.

The Idaho Legislature followed with the creation of the flood control district legislation months later in 1971, leading to other flood control districts being formed in Idaho. Other districts that formed included the Snake River Flood Control

District No. 1, Little Wood Flood Control District No. 2, and Big Wood Flood Control District No. 9.

The Idaho Legislature also passed a new statute in 1971 related to stream-alteration activities in the state. Called the Idaho Stream Channel Protection Act, the new legislation brought a new set of rules, enforced by IDWR staff, that guided a permitting process for stream-alteration activities.

Erv Ballou, Assistant Manager of Flood 10, oversaw the IDWR stream channel permitting process from the very beginning. He recalls that the Idaho Legislature was motivated to come up with a state-permitting process in light of the federal Clean Water Act legislation.

“The state didn’t want the feds telling us how to run our programs,” Ballou recalls. “The state legislation allowed us to create our own program, but there would be some basic rules of operation developed by IDWR, and the flood districts would have to follow those rules.”

Prior to that time, farmers or the Corps of Engineers would go out in the Boise River to clear gravel, trees, or debris with bulldozers, causing quite a bit of damage to the river channel, he said.

Under the Corps program, “they called it clearing and snagging,” he said. “A heavy equipment operator would go out there in the river and clear out the gravel bars and trees, and they kind of turned it into a biological desert.”

The original board members of Flood 10 didn’t want to follow the new stream-alteration rules, Ballou remembers, chuckling at the thought of dealing with the hard-nosed farmers. “The old guys wouldn’t listen. But they were forced to change by the permitting process. They couldn’t go into the river and bulldoze everything they wanted to. They didn’t like it, but they would have to change.”

Ballou remembers that Cane would drive his truck over to construction sites and load up chunks of concrete with rebar sticking out the sides, so they could use the concrete chunks to armor the banks of the Boise River. But he required Cane to saw off the rebar so it would not injure anyone floating the river. In earlier times, farmers used old car bodies – described as “Detroit riprap” – to shore up river banks.

“After the floods came, the high water would sometimes float that stuff out into the middle of the river,” Ballou said. “It wasn’t a long-term fix.”

Part 3: Development Pressure Narrows the Boise River Channel

- By: Steve Stuebner

- Feb 21,2021

As the Boise River Greenbelt project started to get more momentum in the 1970s – the project was originally conceived in 1962 by the Boise City Council – more people were paying attention to Flood District 10 maintenance activities on the river, officials said.

As more miles of Greenbelt were built, the riverbanks became more appealing to business and residential developers. At the same time, developers built levees along the Boise River channel in the downtown core to allow development to occur in the old flood plain.

“Up to the 1970s, people were pretty content to not build in the flood plain,” Susan Stacy, author of When the River Rises: Flood Control on the Boise River 1943-1985, said in a 1993 video produced by the Bureau of Reclamation. “And then after the Greenbelt made the river beautiful, popular, and aesthetically pleasing, and people were floating down it, property owners and developers thought, oh, here’s a value. We ought to build houses as close to the river as we can because obviously, people want to be right next to it.”

For example, if the river banks were repaired and shored up on one side of the river, that would push the energy and impact of high water flows toward the bank on the other side or a riverbank farther downriver.

The river’s width was narrowed from an average of 900 feet wide – or three football fields wide – prior to the construction of Anderson Ranch and Lucky Peak dams, with an average peak flow of 10,700 cubic feet per second (CFS), to an average of 140 feet wide (half the length of a football field), and average peak flow of 3,700 CFS.

A Statement of Intent from the Flood 10 commissioners dated August 26, 2003, explains the quandary: “The District believes that land-use changes significantly affect flood plain conveyance and storage, affecting individual sites and reaches above and below these sites,” the statement says.

“Development in the flood plain, combined with lack of channel-forming flow events, sediment erosion and deposition, and the growth of gravel bars and associated vegetation, reduces the conveyance capacity of the Boise River and increases flooding risks.”

“The most pressing issue facing the District in the future – minimizing flood impacts in the face of rapid growth – requires river maintenance and protecting unimpeded access to the river,” Flood 10 commissioners said.

In the late 1980s, more pressure came from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, the Idaho Division of Environmental Quality and Idaho Rivers United (IRU) to ensure that any streambank work or stream-alternation projects to address flood damage were done in a way that met state and federal law.

“By then, there were more eyes on the river than ever before,” said Erv Ballou, Assistant Project Manager of Flood 10. Ballou reviewed stream-alteration permits for 39 years for the Idaho Department of Water Resources. “Fish and Game and IRU would review the stream-channel alteration proposals, put them under the microscope, and then they’d give feedback to us at IDWR,” he said.

Conservation and fishing groups wanted to maintain more woody debris on the stream banks for trout habitat. They were concerned about how much gravel could be removed from the river, the impacts of heavy equipment on the river environment, etc.

“There was a real evolution in river management during that time,” Ballou said. “We had the direction from the IDWR Director and the Legislature to allow the river work to occur, but we told Flood 10 and anyone else trying to do riverbank repairs, you’ve got to do it right.”

While working for IDWR, Ballou recalls working with the cities and the county to push for wider development setbacks than were approved along the Boise River to allow for flooding and flood repairs and reserve space along the river’s edge for riparian habitat.

“I was asking for 75- to 100-foot setbacks minimum, but the planning and zoning officials were telling me 25 feet is the best we can do. In some places, the set back is only 10 feet between the water’s edge and the Greenbelt.”

By this time, Flood 10 had its first paid staff member, LaRue Bevington, in 1987, serving at the pleasure of the three commissioners guiding the flood district at the time. The paid staff allowed the district to focus more attention on winter maintenance activities, secure stream-alteration permits for the maintenance work, and coordinate with other governmental entities that oversee growth and management of the Boise River corridor.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, thousands of homes and many office buildings were built along the Boise River corridor. The Greenbelt expanded west to Eagle, with a long-term goal of connecting to Eagle Island State Park. Much of the Greenbelt has become a “floodway,” a buffer of sorts between the river and buildings or homes nearby.

BOISE RIVER 2000 DIVERSIFIES VIEWPOINTS ON BOISE RIVER MANAGEMENT

The Boise River 2000 study helped bring people and stakeholders with diverse points of view together to discuss river management issues, looking ahead to future needs.

Flood 10 Chairman Bill Clayton remembers talking to a number of groups like IRU and others about Boise River management in those days.

“I’d start with my black hat on, and I’d say, I’m chairman of Flood District 10, and we cut trees out of the Boise River. And then I’d put on my white hat and say, I’m also a catch-and-release fly fisherman, and I’m committed to preserving the natural character of the Boise River channel. Believe it or not, we can do both and enhance the river in the future.”

As the different stakeholders met together over several years, they developed friendships and relationships of trust. “We have to recognize that we’re not all necessarily enemies here,” Tom “Chel” Chelstrom of Boise remembers telling the Boise River 2000 committee. “Recreation and business can be partners in keeping a healthy river and improving the river.”

Added Clayton, “We must step forward with a long-term solution so we can look at habitat, water users, flood control, recreation – all at the same time. I think we are getting there.”

Part 4: Snowmageddon 2017 – 101 Days of Flooding on the Boise River

- By: Steve Stuebner

- Feb 21,2021

The big flood event of 2017, when the Boise River reservoirs filled quickly with mountain snowmelt in that epic winter termed “Snowmageddon,” forced federal water authorities to release more than 7,000 cubic feet per second of water flow down the Boise River for 101 days from April to late June, as measured at Glenwood Bridge in Boise.

More than 12,000 CFS were being released from Lucky Peak Dam by the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation, and 2,000+ CFS was diverted into the New York Canal and Lake Lowell. High flows caused the Boise River to flood multiple locations along the river corridor, with flows spiking to 9,500 CFS several times in May. The flood stage is 6,500 CFS or higher.

If the weather had heated up to the 80s or 90s during that spring, the flows could have reached 10,000 CFS or higher at Glenwood Bridge, officials said, causing widespread flooding. Fortunately, temperatures remained cool and the melt-off-occurred slowly.

However, it was a grim and necessary reminder that the Boise River can cause flood damage on a periodic basis, officials said. And it clarified the importance of river-maintenance activities carried out by Flood District 10.

to prevent damage to public and private property, including highway bridges.

“People were laser-focused on every possible tree or snag in the river that could get hung up on a bridge or other obstacles and become a safety hazard. It was a very tense, nip-and-tuck situation every day,” said Mike Dimmick, District Manager for Flood 10.

Former Gov. Butch Otter urged local authorities to work together to prevent major damage. “We take this responsibility very seriously,” Otter told the Idaho Statesman. “City, county, state, and federal disaster response personnel are working together to reduce the threat while keeping the public informed and prepared for the potential of more serious flooding.”

That year, more than $2 million in damage occurred to the Boise River Greenbelt, untold amounts to flooded-out mobile homes and residences, and in a very wise move, the Plantation Island Greenbelt bridge was hoisted off its footings for safety reasons. Rapidly eroding gravel around the bridge abutments created enough concern to evacuate the bridge.

The 2017 flood caused a great deal of riverbank erosion, creating a “pit-capture” from the river into a residential pond in Eagle, and it re-arranged river cobble and gravel up and down the river corridor. The Army Corps of Engineers installed miles of barrier walls along the Boise River by a number of gravel pits to prevent floodwaters from reaching the Boise Wastewater Treatment Plant. Flood 10 officials worked closely with Ada County, the Corps of Engineers, and the Idaho Office of Emergency Management to help organize sandbagging, emergency repairs, and bridge clearing.

“Communities along the Boise River were salvaged by a heroic community effort,” notes Andy Tranmer, a professor in the College of Engineering at the University of Idaho who has been studying sediment flows on the Boise River for Flood 10. “The deft operations of the Corps of Engineers and the local community, as well as fortuitous weather conditions allowed us to avoid a disaster with potentially major residential and commercial flooding.”

The same year, floods caused significant damage to riverbanks on the Weiser, Big Wood, Little Salmon, and other rivers and farmlands statewide. That led Flood 10’s attorney, Dan Steenson, to propose state legislation to assist local communities in repairing flood damage in a timely manner.

IDAHO FLOOD MANAGEMENT GRANTS – A “GAME-CHANGER”

In 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was very slow in responding to flood damage claims in Idaho, taking more than a year to respond. “FEMA was overwhelmed with claims from Hurricane damage in Texas, Louisiana, and the Virgin Islands,” Dimmick noted. “It would take them two years to process some claims.”

Steenson and the Idaho Water Users Association advocated for a state flood-management grant program, with $1 million in funding. The Idaho Legislature approved the program in full. The Idaho Water Resource Board was charged with managing the program. A maximum of $200,000 would be allowed for individual grant projects, with a 50 percent match required.

“That was a game-changer for flood-mitigation work in the state of Idaho,” Dimmick says. “With state flood-management funds, we can act much quicker to address the damages caused by floods.”

creating potential for damage to private homes in the area.

In the first year of the program, Flood 10 applied for a state management grant to address four major riverbank repairs needed along the Boise River, including the pit-capture problem in Eagle. In the largest project, Flood 10 worked together with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to restore more than 200 yards of the riverbank with heavy rock and rock barbs. The design integrated root wads and willows into the rock work for additional stability and improved trout habitat.

project with Flood 10, NRCS and the Idaho Water Resource Board.

“This project involved rebuilding a bank that was completed destroyed (by the 2017 flood),” said Doug Higbee, an engineer for NRCS. “We’re putting it in so not only is it stable, and can survive another flood event with water overtopping the bank. We’ve got willow plantings, cottonwood pole plantings, root wads put into the channel, and grass seeding on top of the bank. In many years to come, you’ll be able to come back here, and it will look like a natural part of the river system.”

In 2019, Flood 10 officials applied for a flood-management grant that led to the development of a 2-Dimensional Model Tool for the Boise River. Normally, flood management projects were supposed to address repairing flood damage, but Flood 10 wanted to be more proactive and develop a forward-thinking computer model tool for the Boise River.

simulations of Boise River flood flows to gauge potential impacts next to the river.

The 2D model tool would include collecting high-resolution Lidar imagery along the river corridor to identify trouble spots of major gravel bars, trees, and debris that need to be addressed. The imagery also provided detailed images of the river below the water’s surface to reveal water depth, fish habitat, and other river features that could be helpful for management decisions.

The Idaho Water Resource Board funded the application, sensing that the 2D model tool could potentially benefit other river basins in Idaho.

Flood 10 officials have been working with Tranmer for several years on a sediment study, tracking the movement of river cobble and sediment in the Boise River corridor over time, from Lucky Peak Dam to points west of Caldwell. Tranmer leads the Center for Ecohydraulics Research at the UI College of Engineering.

That study, combined with the 2D Model Tool, informed the need to address specific problem areas along the river corridor where excessive sediment buildup or gravel bars were becoming looming threats that would cause damage to private and public property, officials said.

“Without knowing what is happening across the entire river system, it is very challenging to predict how floods will impact the community,” Tranmer says. “But now we have the new modeling system to help.”

Flood 10 is contracting with the Army Corps of Engineers to develop the 2D Model Tool, now being finalized in the spring of 2021. It’s a big project, exceeding $900,000, starting with a $160,000 flood-management grant from the Idaho Water Resource Board and $100,000 from Flood 10. Other project partners include NRCS, the cities of Boise, Garden City, Eagle, Caldwell, Middleton, ACHD, Eagle Sewer District, Treasure Valley Water Users, and the Pioneer Irrigation District.

District Manager of Flood 10

By bringing together all of those partners, Dimmick hopes the 2D model tool will help coordinate more proactive management of the Boise River.

Another initiative that has occurred recently is identifying trout-nesting sites in the gravel of the Boise River through coordination with Idaho Fish and Game and the Boise Valley Fly Fishers to ensure that heavy equipment does not harm those sites, known as redds. Detailed information plotted on Boise River maps helps Flood 10’s contractors know what areas to avoid.

Flood 10 and BVFF worked together recently on a spawning habitat-improvement project in a side channel of the river. They added some fine gravel, donated by Sunroc, to the side channel that’s more optimum for fish spawning.

corner in the Boise River as it flows into Caldwell.

“We’re also going to relocate some woody debris in the sides of the channel so when the trout fry come out of the gravel, they’ve got a place to hide from predators and grow,” says Troy Pearse, a member of Boise Valley Fly Fishers. “There aren’t that many side channels in the Boise River corridor where fish can spawn. So this is a great opportunity to grow more brown and rainbow trout. We appreciate Flood 10’s help with this project.”

All of these types of efforts will allow Flood 10 Chairman Bill Clayton to realize his dream of getting ahead of the curve, managing the Boise River in a proactive fashion. He’s been at the helm of the Flood 10 board since 1989.

“It’s really important to bring all of those stakeholders together so that we can all get more on the same page about how we’re going to manage the Boise River into the future,” Clayton says.

“We all have to work together, and to do that, we’ve got to keep our eye on the ball with respect to managing the Boise River. It’s a dynamic process, and as much as we might try to stop it or manage it, the Boise River is going to flood again, and we’d better be ready.”